Ringworm is a fungal infection of the skin and hair. Ringworm spreads rapidly, and is zoonotic which means that it can spread from animals to people.

How do animals get ringworm?

The ringworm fungus can cause infection when there is a minor break in the skin or exposure to ongoing moisture and skin damage.

As the fungus lives on infected individuals and in soil, animals can get ringworm from direct contact with other infected individuals and/or from the environment. Fungal spores shed on hair or skin cells can survive for many months in the environment, especially in hot, wet, humid conditions. With climate change, the risk of fungal infections such as ringworm is increasing.

Young, old and undernourished animals, and individuals who are sick or have a weak immune system are most at risk of ringworm. For cats, the risk increases for long-haired varieties. Ringworm is more likely to occur where animals are stressed, crowded together (e.g. , shelters, catteries), where management is poor, and where new animals are mixed together without a quarantine period.

How do I know if my animal has ringworm?

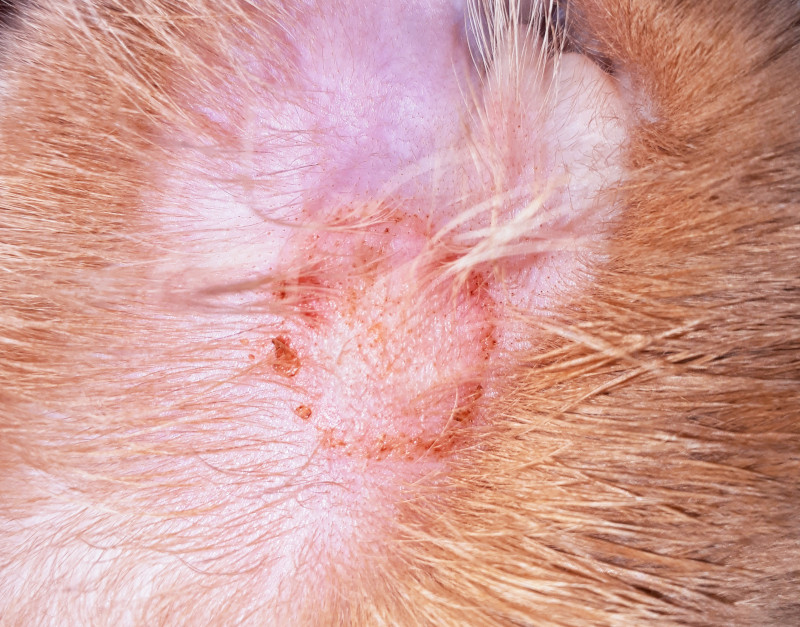

Typical signs of ringworm are a circular area of hair loss, scaling of the skin and a classic red ‘ring’ on hairless areas of the body. Ringworm can be in one area or all over the body. It is not itchy. Infected hairs can become brittle and break off. Cats can also become chronic carriers of ringworm, infecting others without showing any signs except during periods of stress.

If you notice any signs of ringworm on your companion animal, seek prompt veterinary attention to allow diagnosis and treatment.

How can ringworm be prevented and treated?

Ringworm is treatable. Seek veterinary advice about the best treatment options, and how to prevent the spread of ringworm to others in your household.

After receiving a diagnosis that your animal has ringworm, you should separate them from other animals in the household and practise additional hygiene measures (e.g., hand washing after touching them).

If you want information on ringworm in humans, or what extra precautions should be taken if you are at risk of being infected, seek advice from your doctor.

Reference

Moriello, K. A., Coyner, K., Paterson, S., & Mignon, B. (2017). Diagnosis and treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs and cats.: Clinical Consensus Guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Veterinary Dermatology, 28(3), 266–e68. https://doi.org/10.1111/vde.12440