Considerations for reptile enclosures include:

- What sort of reptile am I planning on having?

- Free range or confined?

- Construction materials

- Size and shape

- Substrate

- Cage furniture

- Heating and lighting

- Humidity

- Ease of cleaning

- Security

What sort of reptile am I planning on having?

This is a fairly basic consideration, but important nonetheless. Will your reptile want to climb? If so, a taller enclosure might be better. How big will the reptile grow (not how big are they now)? How active are they likely to be? Snakes are ‘ambush predators’ – they lie in wait for their food – while lizards are ‘hunter predators’, they go looking for their food. All these species-specific considerations are key to providing your reptile with an enclosure that meets their physical and mental needs. For more information see this article.

Free range or confined?

Reptiles should not be allowed to roam free indoors. The floor is the coldest area of the house, which may lead to hypothermia and inappetance (loss or lack of appetite). Free ranging reptiles can be exposed many external risks such as crushing injuries when caught in a closing door, being stepped on, or being bitten by other pets. Animals may escape through an open door or fall from the stairs or a balcony. There is also a risk of your reptile shedding Salmonella into your environment, posing a potential health risk to you, your family and other pets. These problems can be avoided using a well-designed enclosure.

Vivarium — an enclosure for keeping animals under semi-natural conditions (plural vivaria).

Terrarium — a vivarium for smaller land animals, such as reptiles, usually in the form of a glass-fronted enclosure (plural terraria).

Materials

Construction materials should be impervious to water, easy to clean, and not allow a build-up of bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Abrasive materials and wire-mesh should be out of reach of animals. Coverings of walls should be fitted in such a way that animals cannot be trapped behind them and that food animals (such as insects) cannot hide. Note that there are potential welfare and ethical considerations with the feeding of live insects to reptiles to think about; for more information see this article.

Covering the floor of terraria with a smooth glass-fibre enforced epoxy-resin surface that is free from cracks and prevents accumulation of bacteria on the back of the covering.

Size and shape

- Size: Novice reptile keepers frequently make the mistake of transferring a hatchling or small reptile to a large vivarium. Snakes should always be housed so that they can stretch to their full body length (their primary enclosure must be longer than they are when fully extended); lizards need room to move. However, very large enclosures may make it difficult for a small reptile to regulate their body temperature and they may become disoriented and unable to find food or water. Small plastic pet containers are sufficient for hatchling pythons. Subfloor heating is usually provided by heat mats or tape. According to some authors, the size of the cage may not be as important as how it is furnished (see below).

- Shape (length vs height): As a rule, arboreal reptiles (tree dwellers) need a tall enclosure while terrestrial reptiles (ground dwellers) need a long enclosure.

See the section below on Codes of Practice to obtain more specific advice on enclosure size and shape.

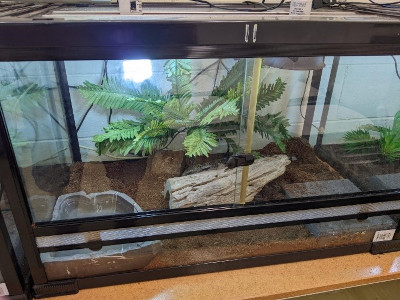

Substrate

Appropriate substrates (the surface on which the reptile lives) vary according to the special needs of a species. Newspaper is suitable for arboreal species such as diamond and carpet pythons. Terrestrial species such as Children’s pythons and blue tongues do best on pelleted newspaper “kitty litter” products. Hatchling and small pythons should not be fed in containers with pelleted newspaper substrate. Pellets may be inadvertently swallowed, causing intestinal obstruction. The feeding area should be a separate container lined with paper. Bearded dragons thrive on fine sand. Gravid females (those carrying eggs or young) need a suitable substrate for digging and egg laying.

Artificial turf, bark chips, and dirt are unsuitable, as they are difficult (impossible) to clean and, so, provide good media for bacterial and fungal growth.

Enclosure/cage furniture

Many reptile species are naturally timid and need to have access to hiding places to avoid becoming stressed. Some reptiles never adapt to captivity and will always seek to hide when a person approaches. You can provide shelter in the form of a hollow log or a small box with a narrow entrance (a hinged lid will allow access for cleaning etc).

All captive reptiles need somewhere to hide, these are usually called “hides” but are also sometimes called reptile caves. Items such as toilet rolls, or small cardboard boxes are ideal for hatchling snakes and the smaller terrestrial reptile varieties to hide in. When these items become soiled, simply replace them. Porcelain hides and inverted flowerpots are also popular. These structures must be waterproof and easy to disinfect. Certain species are more secretive compared with others e.g., Antaresia spp (Children’s pythons).

Large enclosures should be furnished with several hides in a variety of positions to facilitate thermoregulation. Care must be taken that large leafy plants used in some enclosures as hides do not raise the humidity levels underneath them. For more information see this article.

Hides can also be used as an aid to handling. This is especially relevant to more aggressive or venomous species. The entrance to a favourite shelter may be blocked securely and then used to transport the reptile.

Heating and lighting

In contrast to birds and mammals, reptiles have evolved as ectotherms – animals who regulate their body temperature to suit the temperature around them. They are not poikilothermic (cold-blooded) as most people commonly believe – while their body temperature is dependent upon external heat sources rather than internal heat production, most are capable of very precise control of their body temperature. Because of this, you should give careful consideration to what sort of heating and what temperature your reptiles should be kept at.

It is commonly said that pet reptiles should get a few hours (at least) outside in the sun. Artificial lighting is also used indoors, trying to replicate sunlight. But why do reptile keepers go to such lengths?

Sunlight contains so-called white light (light that contains all the wavelengths of visible light at approximately equal intensities), as well as ultraviolet light. Both are important to the health of your reptile.

Humidity

Humidity requirements vary with species (40-80%). For example, the environment of a green python (Morelia viridis) needs to be much more humid than that of the inland bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). All snakes need a large water bowl for bathing and drinking. The humidity of a vivarium can be controlled by altering the size of the water bowl. Always place it at the cooler end of the enclosure, except in cases where a rapid increase in humidity is required. In these cases, a heat lamp or mat may be placed under the water container to aid evaporation. All vivaria, dry and humid, should be adequately ventilated.

Ease of cleaning

Poor hygiene is a leading cause of poor health in captive reptiles. The increased concentration of pathogens in an artificially small environment can contribute to the development of serious health problems in reptiles, particularly if the reptile is already immunosuppressed by stress and/or malnutrition. Regular cleaning (as distinct from spot cleaning) is essential, as well as designing an enclosure to facilitate easy cleaning.

Security

It is important that enclosures are secure not only to prevent the escape of the reptiles but to prevent pets and children from getting in. Security is obviously extremely important with snakes. An escaped snake turning up in your neighbour’s house can be dangerous (for your neighbours and for your snake!) and is unlikely to endear them to you or make them feel sympathetic towards you keeping reptiles. A secure, well ventilated, easily maintained enclosure is best.

Codes of Practice

Most states in Australia have developed (in consultation with stakeholder such as animal welfare organisations like the RSPCA, veterinarians, and animal owners) a range of Codes of Practice for the welfare of animals. These codes contain guidelines and information about the considerate and humane treatment of animals. Most of these guidelines contain information on:

- feed and water

- housing

- health

- management practices

- breeding

Most of these codes are voluntary (only a few are compulsory). This means that you MAY follow the guidelines they contain. If you don’t follow them, you may have to demonstrate how you have met the requirements of the various Animal Welfare/Animal Protection Acts i.e., how you have met your duty of care.

These codes of practice are fairly unique – many countries around the world have nothing similar but would like them. They provide a basic (but minimal) outline for how to care for your reptile.

Note: Information current as of 15 June 2023. This information is not legal advice. Seek advice from the relevant authority.

References

Baines F (2018) Lighting. In: Doneley B, Monks D, Johnson R, Carmel B (eds) Reptile medicine and surgery in clinical practice. Wiley-Blackwell, pp 75–90

Cargill BM, Benato L, Rooney NJ (2022) A survey exploring the impact of housing and husbandry on pet snake welfare. Animal Welfare 31:193–208

Carmel B, Johnson R (2014) A guide to health and disease in reptiles & amphibians. Reptile Publications, Burleigh

Hoehfurtner T, Wilkinson A, Walker M, Burman O (2021) Does enclosure size influence the behaviour & welfare of captive snakes (Pantherophis guttatus)? Appl Anim Behav Sci 243:105435

McFadden M, Monks D, Johnson R (2018) Enclosure design . In: Doneley B, Johnson R, Monks D, Carmel B (eds) Reptile medicine and surgery in clinical practice. Wiley-Blackwell, pp 61–73

Warwick C, Grant R, Steedman C, et al (2021) Getting it straight: Accommodating rectilinear behavior in captive snakes—a review of recommendations and their evidence base. Animals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11051459