What is the RSPCA’s view on killing sharks to reduce shark incidents?

The RSPCA does not support killing sharks as a response to shark incidents involving humans. This approach causes unnecessary animal suffering to both target and non-target species. In addition, culling disturbs marine ecosystems and affects protected and vulnerable species including the targeted great white shark and non-target species such as the grey nurse shark. The available scientific evidence does not convincingly support the claim that killing sharks will reduce the risk to public safety. The RSPCA only accepts the management of wild animals where it is justified, effective and humane; the killing of sharks does not meet these criteria.

Note: A ‘shark incident’ is a human-shark interaction that results in injury or death of a human.

How and why are sharks killed?

Since 1937, New South Wales has been actively killing sharks in an effort to help reduce shark incidents [1]. In response to a spike in human fatalities from shark incidents over the past few years, state governments have been considering a range of policies to help reduce this threat. These policies involve catching, trapping and/or killing sharks off the coast near popular beaches considered to be at risk of shark incidents.

Various methods are used to help reduce the threat of shark incidents including drumlines, SMART drumlines and shark nets all of which inevitably result in the death of some target and non-target species. Non-lethal options are also available but used to a much lesser extent (e.g. personal protective devices, increased surveillance and alert systems etc).

Are shark incidents increasing?

The recent increase in shark incidents is not due to increasing shark numbers, as there is evidence that there has been a significant decline in coastal apex predators over the past 50 years. For example, a study conducted on the east coast of Australia indicates that the number of Great White Sharks has declined by 92% [2]. Rather, the increase in shark incidents is consistent with a changing and increasing human population.

Although the average number of shark incidents has increased in Australia over recent decades – during the 1990s the national average was 6.5 unprovoked incidents per year but this has risen to 12.5 in the early 2000s [3], the risk of human injury or death from a shark encounter is still very low.

The Australian Shark Incident Database reports that in the last 50 years there have been 50 unprovoked shark incidents resulting in fatalities in Australian waters. Some years there are no fatalities recorded and in other years there have been up to five, but the average remains around one per year.

The International Shark Attack File reports that with great white sharks, the increase in incidents is a reflection of increased numbers of people using the ocean, and the increased awareness of incidents is a result of enhanced media coverage over the last century. The statistics on shark incidents does not support an increase in the ‘per capita attack rate’ by great white sharks.

Although the number of reported shark bites has increased, the fatality rate has decreased due to improved medical response, greater public knowledge of basic first aid and resuscitation, and increased education about shark incidents. Fatalities usually occur at remote beaches or where medical assistance may be delayed.

What methods are used to try to reduce shark incidents?

Drumlines

A drumline consists of a floating drum (a rubber buoy) with one line attached to an anchor on the sea floor, while a second line features a large, baited hook to lure, catch and ultimately cause the death of sharks. Currently in Queensland lines are only checked every second day and so it is likely that only a few sharks would be humanely killed, thus sparing them prolonged suffering.

In Western Australia in 2014, a trial was conducted where drumlines with baited hooks were set approximately 1km from the coast in designated ‘marine monitored areas’. Over the 13-week trial, 68 sharks were caught by the drumlines and shot; none of them were great white sharks. An evaluation by the state’s Environmental Protection Authority recommended that the drumlines be abandoned as it was not effective in achieving its objectives [4]. Drumlines have not been re-introduced in WA.

SMART drumlines

In 2017, a Federal Senate inquiry recommended that traditional drumlines be replaced with SMART (Shark Management Alert in Real Time) drumlines, and that shark netting programs be phased out [5]. A SMART drumline is designed to be a non-lethal method which, via a satellite link, sends an alert when the baited hook has been ‘taken’, with the aim that the shark or other species will be retrieved within a short period of time to enable live release. Target species and bigger non-target sharks of interest are generally released at least one kilometre from the SMART drumline.

From 2019 to 2020, the Western Australian government evaluated SMART drumlines and concluded that the technology was not an effective shark mitigation strategy in WA conditions. Over the two-year trial period, only two white sharks (target species) were caught but 266 non-target sharks (including tiger and bronze whaler sharks) and 43 other non-target marine animals were caught [6]. The low efficacy combined with the poor welfare prompted the Western Australian government to invest in research to improve current available technologies and implement more welfare-friendly and effective solutions such as aerial surveillance, beach enclosures and incentives for personal protective devices [7].

SMART drumlines are still used in NSW. The NSW Department of Primary Industry (DPI) reported that between 2015 and 2018, the SMART drumline program resulted in the interception of 300 White sharks, 43 Tiger sharks and 27 Bull sharks. Captured sharks in NSW are tagged and tracked. 149 non-target species were also captured. The DPI has acknowledged that the best mitigation strategies for shark incidents are on a personal level through education, behaviour change and/or the use of personal deterrents [8].

Shark nets

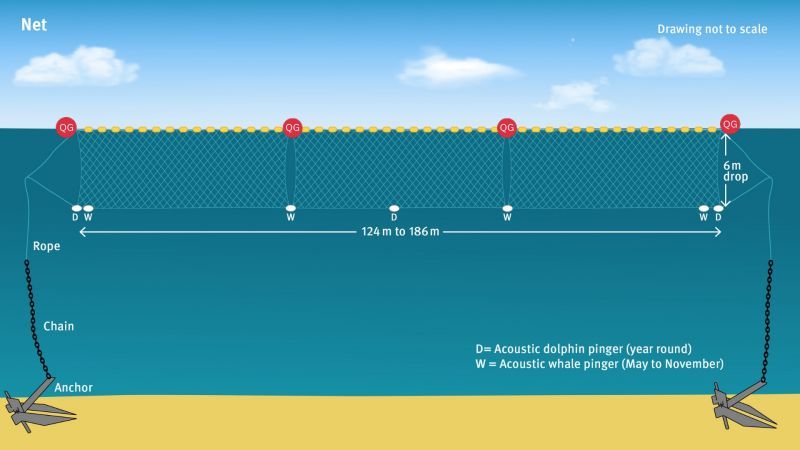

A shark net is a submerged net placed around swimming beaches to reduce shark attacks by catching sharks, with most succumbing due to entanglement and drowning. It has also been reported that shark nets may create a false sense of security for swimmers as they do not provide a complete barrier against sharks. Figure 1 illustrates the coverage of shark nets used in Queensland which only cover the top half of the water column.

Figure 1: Diagram showing use of shark net.

In 2022/23, it was reported that of the 228 animals entangled in nets in NSW, 80% were either threatened, protected or non-target species (120 non-target sharks, 58 rays, 14 turtles, eight dolphins and two seals) [1]. Furthermore, there is a risk that dead and dying marine life caught in nets can attract sharks, potentially increasing the risk to humans. In Western Australia, beach enclosures have been adopted as an alternative. Compared to nets, these barriers cover the full water column (anchored to the seabed and connected to floats at the surface) and prevent sharks from entering without causing entanglements [7].

In NSW, 51 beaches between Newcastle and Wollongong are netted [1]. The latest annual performance report in NSW indicated that 94% of interactions with shark nets were non-target species, with 25% of those involving threatened or protected species. Target sharks (White, Bull and Tiger sharks) accounted for only 6% of interactions [1]. Unlike Queensland where nets are removed during the winter months to help reduce the risk of entanglement by migrating humpback whales, NSW currently allows nets to remain all year round.

Is killing sharks effective in reducing shark incidents?

A 2017 federal Senate inquiry into shark mitigation and deterrent measures concluded that lethal methods are not proven to improve public safety, and that new and emerging technologies have been shown to provide effective protection without causing negative environmental impacts [5]. These include advances in aerial surveillance, sonar technology, beach eco-barriers and deterrents (personal and ‘whole of beach’).

Furthermore, in 2019, the Queensland Administrative Appeals Tribunal accepted evidence presented by Humane Society International that mesh nets and drumlines used by programs implemented by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) do not improve human safety, negatively impact on the marine ecosystem, and provide beachgoers with a false sense of security [9]. Based on this evidence, DAF were instructed to significantly modify their shark management program including ensuring that sharks must be attended to within 24 hours of being caught on drumlines and are only to be euthanased on welfare grounds. However, this time delay is likely to result in injury and death of caught species (target and non-target) and significantly contrasts with the WA Non-lethal SMART Drumline Operating Manual, where a boat must be at the site within 30 minutes of an alert and set SMART drumlines are to be checked every three hours or in NSW, where SMART Drumlines are set only during the day and alerts are attended to immediately.

Whatever approach is taken, for shark management programs to be effective at reducing shark incidents, they must be based on the best available scientific evidence.

Is it legal to kill protected sharks?

Normally, a permit to harm protected wildlife under the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) must be obtained prior to killing any protected wildlife. In 2014, the WA government was granted an exemption from gaining this permit to kill sharks by the Federal Environment Minister. The 2017 federal Senate inquiry into shark mitigation and deterrent measures recommended that no further exemptions be granted until a review of the EPBC Act is undertaken. This is important because there is evidence that shark numbers are declining based on declining catches in nets set as part of the Queensland Shark Control Program [2]. There is concern relating to lower numbers of hammerhead, tiger and great white sharks, as a reduction in apex predators will impact ecological processes and balance. However, because the shark management programs in Queensland and New South Wales have been operating for many years, both states do not require approval to kill protected sharks. Furthermore, the current Queensland Shark Control Program (QSCP) cannot be prosecuted for animal cruelty charges on the basis of an exemption of the Animal Care and Protection Act 2001 (Queensland) which allows the use of fishing apparatus which protect persons from attack by sharks.

The RSPCA believes that proper assessment processes must be followed when any proposal is made to kill or otherwise harm wildlife, and especially when one of the target species is vulnerable to extinction. These processes are crucial to ensure that decisions are based on the available science and that conditions are in place to ensure any control measures are carried out in the most appropriate way to ensure that risks to the welfare of both target and non-target species are mitigated.

What can be done to help reduce shark incidents instead of killing sharks?

The RSPCA supports the implementation of justified, humane and effective methods to prevent shark incidents. When evaluating potential mitigation methods, welfare aspects relating to target and non-target species must be considered in addition to environmental assessment. It is recommended that non-lethal methods that are informed by an understanding of shark biology, behaviour and ecology are further developed and implemented, including (but not limited to):

- tagging and tracking alert systems,

- patrols and surveillance [10],

- active and passive electrical repellents [8],

- innovative sonar systems and

- eco-barriers.

Shark awareness programs [11] that educate the public about risk factors that can potentially influence the likelihood of being attacked by sharks also play an important role.

Future options

Sharks play a vital role in maintaining the health of our oceans, yet they face significant threats due to misconceptions and fear. Despite the rarity of encounters between ‘dangerous’ sharks and humans, these animals are often subject to measures that put them at risk of suffering and death. A recent NSW survey showed that, whilst 50% of regular ocean users express concerns about shark encounters, only 16% are supportive of additional funding for shark mitigation strategies, with 40% and 29% preferring funds be devoted to ocean cleanliness and drowning prevention respectively [12].

As we strive to protect both sharks and people, it is essential to explore future options for shark control that prioritise welfare-friendly approaches. Some options include:

- Personal protective wetsuits – new technologies have been developed over the past decade that can deter sharks or minimise consequences of shark bites. Shark deterrent devices include ecofriendly shark-repellent sprays, as well as wrist bands or surfboard accessories that can create magnetic or electrical fields that disrupt the shark’s sensory receptors. New wetsuit technologies have also been developed that can deter sharks due to their visually-disruptive striped designs mimicking the pattern of poisonous fish, rather than the more common dark grey/black wetsuits that resemble seals [13].

- Puncture-proof and tear-proof wetsuits – these are another innovative approach aimed at mitigating the severity of shark incidents by minimizing blood loss and injuries resulting from shark bites. While they do not serve as a direct means of deterring sharks, they provide individuals with valuable time for medical aid to be administered in the event of an incident [14]. Whilst not 100% effective, these technologies help deter sharks and significantly reduce the severity of injuries. Thus, these technologies contribute to overall human safety while minimizing harm to sharks and more efforts should be placed on improving these technologies and their efficacy for a welfare friendly approach.

- The Sharksafe barrier – this is a new technology that employs two stimuli, a visual barrier made of artificial kelp and an electro-sensory barrier generated by magnets. The combination of these two stimuli has been shown to effectively alter the behaviour of great white sharks increasing avoidance and decreasing entrance frequency. This new technology shows promise as a resilient, environmentally friendly, humane and non-invasive shark mitigation strategy that acts by altering shark behaviours without negatively impacting other marine species [15].

References

NSW DPI (2023) NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2022-23 Annual Performance Report (nsw.gov.au).

West JG (2011) Changing patterns of shark attacks in Australian waters. Marine and Freshwater Research 62(6):744–754.

Roff G, Brown CJ, Priest MA et al (2018) Decline of coastal apex shark populations over the past half century. Communications Biology, 1:223.

Western Australia Shark Hazard Mitigation Drum Line Program 2013-14 (2014) Government of Western Australia.

Environment and Communications Reference Committee (2017) Report of Senate Inquiry Shark Mitigation and Deterrent Measures. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

DPIRD (2020) Results of the non-lethal SMART drumline trial in south-western Australia between 21 February 2019 and 20 February 2020. Fisheries Occasional Publication No. 139, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia

Western Australian Government (2024) Shark mitigation strategies. Sharksmart.

Hart NS & Collin SP (2015) Shark senses and shark repellents. Integrative Zoology 10:38-64.

Administrative Appeals Tribunal (2019) Humane Society International (Australia) Inc and Department of Agriculture & Fisheries (Qld) [2019] AATA 617 (2 April 2019) (austlii.edu.au)

Kock AA, Titley S, Petersen W et al (2012) Shark Spotters: A pioneering shark safety programme in Cape Town, South Africa. In: Domeier ML (ed) Global perspectives on the biology and life history of the great white shark. CRC Press, p 447–466.

For example, see NSW DPI SharkSmart program.

Peden AE & Brander TW (2024) Is further investment in shark management in New South Wales worthwhile? Surfer views on coastal public health issues. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 100116.

Huveneers C, Whitmarsh S, Thiele M et al (2018) Effectiveness of five personal shark-bite deterrents for surfers. PeerJ, 6, 35554.

Huveneers C, Blount C, Bradshaw CJ et al (2024) Shifts in the incidence of shark bites and efficacy of beach-focussed mitigation in Australia. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 198, 115855.

O’Connell CP, Andreotti S, Rutzen M et al (2014) Effects of the Sharksafe barrier on white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) behaviour and its implications for future conservation technologies. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 460:37-46.

Was this article helpful?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.