We know that the human families of brachycephalic, or flat-faced, dogs love and cherish these animals. Unfortunately, the exaggerated physical features that often initially draw people to these breeds, like their flat faces, cause health and welfare problems for these animals. The noticeable breathing noises that these dogs make, like snuffling, snoring, and snorting, are signs that breathing is very difficult and distressing for the dog, and this realisation can be heartbreaking.

Animals with extremely exaggerated physical features may require specialised veterinary care to improve their comfort and quality of life. These dogs may also need additional lifelong daily care from their owners. Potential owners should carefully and seriously consider their capacity to provide adequate, often ongoing, care for a brachycephalic dog. This includes considering financial circumstances, having access to a specialist emergency veterinary clinic, likelihood of travel or relocation, and participating in an active or busy lifestyle.

Features of brachycephalic animals

Brachycephalic animals, including dogs and cats, have an exaggerated foreshortened skull resulting in the characteristic flattened short-muzzled face of brachycephalic breeds [1]. These abnormalities are a result of selecting physical features for a specific appearance, rather than selecting for traits that will maintain or improve the health and welfare of the animal. Brachycephalic dog breeds include pugs, British and French bulldogs, Boston terriers, and others [1–3].

Brachycephalic dogs can suffer from a range of health and welfare issues including breathing problems, digestive issues, eye diseases, difficulty giving birth, spinal malformations, exercise and heat intolerance, sleeping difficulties, skin and ear diseases, and dental disease [1–3].

Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)

Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS) is a disorder commonly seen in brachycephalic dogs, in which obstruction of the airways results in breathing difficulties and significant compromise to the dogs’ welfare and quality of life [2–4]. BOAS is a lifelong and often progressive disorder that affects a dog’s ability to live comfortably and engage in normal dog behaviours. BOAS-affected dogs show a variety of clinical signs including difficulty breathing, noisy breathing (and snoring), exercise intolerance, coughing, gagging, regurgitation, passing out, and hyperthermia [2, 3]. BOAS can affect the dog’s ability to engage in normal behaviours and daily activities (see more detail below). Common breeds that are affected by BOAS include the French bulldog, Pug, British bulldog, and Boston Terrier [1, 3, 5].

Dogs with BOAS may require surgery to reduce the obstruction of their airways and help improve their breathing, health, and quality of life [5, 6]. However, even though many brachycephalic dogs can have their lives improved by surgery, it is not a ‘silver bullet’ and dogs may still require lifelong management of their condition [5]. Unfortunately, the majority of dogs still experience some respiratory compromise even if they have had corrective surgery [2, 7]. In addition, there are risks with the sedation and anaesthesia of brachycephalic dogs, regardless of whether they are undergoing sedation or anaesthesia for a BOAS-related surgery or an unrelated surgery or procedure [3, 5]. These risks should be discussed with a veterinarian.

BOAS is also thought to increase the health risks associated with air travel for brachycephalic dogs, during which some animals have tragically died [2]. This has resulted in some airlines refusing to accept these animals for air transport or imposing strict guidelines for airline travel due to the high risk of serious health problems and death [2].

Brachycephalic Ocular Syndrome

Many brachycephalic breeds suffer from eye problems that are related to their brachycephalic conformation, bulging eyes, and abnormalities relating to their eyes and eyelids [3, 8–11]. The range of eye problems seen in brachycephalic breeds are known collectively as Brachycephalic Ocular Syndrome and include corneal ulceration, dry eye, and eye trauma (including proptosis where the eyeball protrudes out of the eye socket) [8–12]. These conditions negatively impact dog welfare and can cause significant and chronic suffering.

Dogs with Brachycephalic Ocular Syndrome often need surgery, medications, and ongoing management throughout their lives to treat these conditions and minimise pain and discomfort [3, 5, 6].

Difficulty giving birth

Some brachycephalic dog breeds have substantial difficulty giving birth (e.g., Boston terrier, French bulldog, British bulldog, and pug), due to fetopelvic disproportion (the puppies being a size and shape that does not allow them to easily pass through the mother’s birth canal) [3, 13, 14]. This can make veterinary assistance necessary, which may include anaesthetising the mother, then surgically removing the puppies (a caesarean section or C-section) [3, 13, 14]. These are significant health risks and interventions which can result in negative impacts on both the mother and pups’ welfare. Some brachycephalic dog breeds have high caesarean section rates (80% or more) [3].

A caesarean section surgery may be performed as an emergency when a female in labour is unable to safely birth the puppies naturally. Emergency caesarean section (e.g., when a pup becomes trapped in the birth canal) greatly increases risks to mother and pups, including increased likelihood of puppies dying [15].

A caesarean section surgery may be performed as an elective surgery scheduled on a fixed date and time before the onset of natural labour. In some high-risk breeds it is common for elective caesarean sections to be performed [3, 14, 16], due to the known incidence of birthing problems in that breed or family of dogs. Although this is the safest option for high-risk dogs, this is still a significant procedure with potential risks and negative consequences for both mother and pups.

Dogs who undergo caesarean sections are more likely to have trouble giving birth naturally when having subsequent litters [17].

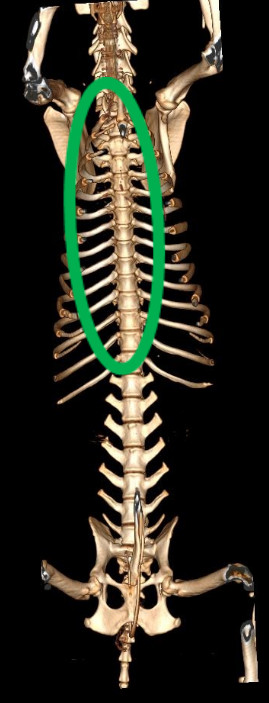

Spinal and tail malformations

Some brachycephalic breeds including the pug, French bulldog, British bulldog, and Boston terrier commonly have a tail malformation, also known as screw tail [18, 19]. A screw tail is a genetic malformation that causes the bony part of the spine forming the tail to have a reduced number of bones (so that it is shortened) and some of the bones fuse together (so that it curls or kinks) [20].

Brachycephalic dogs with screw tails also have a high likelihood of having other deformities along the length of their spine (such as hemivertebra), which can cause health conditions such as nerve problems leading to an inability to move normally, pain along the spine, and urinary or faecal incontinence [21]. One study showed that spinal malformations can be found in up to 83% of some brachycephalic breeds, such as British and French bulldogs [19]. These malformations can potentially cause severe neurological defects which can be very challenging to treat [18].

|

|

Exercising

Brachycephalic dogs may be unable to exercise normally, especially in warmer and more humid weather [2]. In one study, a third of brachycephalic dogs were unable to walk for more than 10 minutes on a 19°C summer day [22]. This inability to exercise normally can severely restrict the walking and play activities these dogs can engage in and share with their owners and inhibits their ability to express the behaviours that dogs enjoy [2].

Weight control is extremely important for brachycephalic dogs, as extra weight and obesity can make their breathing problems much worse [3]. Exercise intolerance poses a major challenge for weight management of brachycephalic dogs. As a result, nutritional management is critical to ensure optimum weight. It is also important that these dogs have regular exercise but this must be managed so that difficulty in breathing is avoided. This regular exercise both helps with weight management and provides important opportunities for socialisation and other positive experiences associated with being outdoors and exploring the world.

Sleeping

Some brachycephalic dogs are unable to sleep normally because their narrowed airways become easily obstructed [3]. This causes sleep disturbances which may have a significant effect on the dog’s welfare [22]. Some dogs may wake up frequently (and may also suffer from ‘choking’ arousals) and/or they may adopt postures that help avoid airway obstruction while they sleep, such as sleeping sitting up, propping their chin on objects and sleeping with an object such as a toy in their mouth [3, 22].

Other issues common in brachycephalic dogs

Many brachycephalic dogs have an increased risk of heat-related illness (such as heat stress and heat stroke), which can have life threatening consequences [2, 23, 24].

Otitis externa (inflammation and/or infection of the ear canal) is common in brachycephalic dogs [3, 25]. This condition can be very painful and, especially if recurrent or ongoing, can be challenging to treat and have long term consequences.

In addition to ear disease, other skin diseases and conditions are also common in brachycephalic dogs including skin fold dermatitis, pyoderma, pododermatitis and atopic dermatitis [3]. Skin conditions can have a significant negative impact on dogs’ quality of life.

Dental problems are common in brachycephalic dogs as they generally have some degree of dental abnormalities due to their brachycephalic skull shape [3, 25]. These include poorly aligned teeth, crowding and rotation of teeth, gum problems, and teeth that do not erupt properly. These abnormalities often lead to periodontal disease and other dental and oral problems that can be painful and negatively impact dog health and welfare [3].

Brachycephalic dogs may also suffer from eating difficulties including choking while eating and regurgitation [3].

Impacts on behaviour

Many brachycephalic dogs are unable to fully and freely engage in normal dog behaviours and daily activities such as playing, exercising, sleeping, chewing, and eating due to physical limitations associated with their airway disease and other conditions such as hemivertebrae [2, 3, 26].

Their exaggerated physical features (such as very short and/or curled tails and prominent facial skin folds) can also inhibit their ability to communicate normally with other dogs, animals, and people [2, 26].

More information

RSPCA Australia and the Australian Veterinary Association are calling for the selection and breeding of dogs to prioritise dog health and welfare. Current and potential owners can play a vital role in helping to improve the welfare and lives of brachycephalic breeds. For more information see Love is Blind, Australian Veterinary Association, and International Collaborative on Extreme Conformations in Dogs (ICECDogs).

References

[1] Packer RMA, Hendricks A, Burn CC (2015) Impact of Facial Conformation on Canine Health: Corneal Ulceration. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0123827

[2] Child G, Mooney E, Brunel L, Barrs V, McGreevy P, Fawcett A, Awad M, Martinez-Taboada F, McDonald B (2018) Consequences and Management of Canine Brachycephaly in Veterinary Practice: Perspectives from Australian Veterinarians and Veterinary Specialists. Animals 9:3

[3] Packer R, O’Neill DG (2022) Health and Welfare of Brachycephalic (Flat-faced) Companion Animals; A Complete Guide for Veterinary and Animal Professionals. Oxon

[4] Neill DGO, Jackson C, Guy JH, Church DB, Mcgreevy PD, Thomson PC, Brodbelt DC (2015) Epidemiological associations between brachycephaly and upper respiratory tract disorders in dogs attending veterinary practices in England. Canine Genet Epidemiol 1–10

[5] Mitze S, Barrs VR, Beatty JA, Hobi S, Bęczkowski PM (2022) Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome: much more than a surgical problem. Veterinary Quarterly 42:213–223

[6] Lindsay B, Cook D, Wetzel JM, Siess S, Moses P (2020) Brachycephalic airway syndrome: management of post-operative respiratory complications in 248 dogs. Aust Vet J 98:173–180

[7] Liu NC, Oechtering GU, Adams VJ, Kalmar L, Sargan DR, Ladlow JF (2017) Outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical treatments for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome in 3 breeds. Veterinary Surgery 46:271–280

[8] Sebbag L, Sanchez RF (2023) The pandemic of ocular surface disease in brachycephalic dogs: The brachycephalic ocular syndrome. Vet Ophthalmol 26:31–46

[9] Lau WI, Taylor RM (2025) The Prevalence of Corneal Disorders in Pugs Attending Primary Care Veterinary Practices in Australia. Animals 15(4):531

[10] O’Neill DG, Skipper A, Packer RMA, Lacey C, Brodbelt DC, Church DB, Pegram C (2022) English Bulldogs in the UK: a VetCompass study of their disorder predispositions and protections. Canine Med Genetics 9(1), 5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40575-022-00118-5

[11] Costa J, Steinmetz A, Delgado E (2021) Clinical signs of brachycephalic ocular syndrome in 93 dogs. Ir Vet J 74(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13620-021-00183-5

[12] O’Neill DG, Sahota J, Brodbelt DC, Church DB, Packer RMA, Pegram C (2022) Health of Pug dogs in the UK: disorder predispositions and protections. Canine Med Genetics 9(1), 4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40575-022-00117-6

[13] Neill DGO, Sullivan AMO, Manson EA, Church DB, Boag AK, Mcgreevy PD, Brodbelt DC (2017) Canine dystocia in 50 UK first-opinion emergency care veterinary practices: prevalence and risk factors. Veterinary Record, 181(4), 88 https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.104108

[14] Runcan EE, Coutinho da Silva MA (2018) Whelping and Dystocia: Maximizing Success of Medical Management. Top Companion Anim Med 33:12–16

[15] Proctor-Brown LA, Cheong SH, Diel de Amorim M (2019) Impact of decision to delivery time of fetal mortality in canine caesarean section in a referral population. Vet Med Sci 5:336–344

[16] Wydooghe E, Berghmans E, Rijsselaere T, van Soom A (2013) International breeder inquiry into the reproduction of the English bulldog. In practice Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 82:82–43

[17] De Cramer K, Nöthling J (2020) Towards scheduled pre‐parturient caesarean sections in bitches. Reproduction in domestic animals 55:38–48

[18] Gutierrez-Quintana R, Guevar J, Stalin C, Faller K, Yeamans C, Penderis J (2014) A proposed radiographic classification scheme for congenital thoracic vertebral malformations in brachycephalic “screw-tailed” dog breeds. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound 55:585–591

[19] Lackmann F, Forterre F, Brunnberg L, Loderstedt S (2021) Epidemiological study of congenital malformations of the vertebral column in French bulldogs, English bulldogs and pugs. Veterinary Record 190:e509

[20] Mansour TA, Lucot K, Konopelski SE, et al (2018) Whole genome variant association across 100 dogs identifies a frame shift mutation in DISHEVELLED 2 which contributes to Robinow-like syndrome in Bulldogs and related screw tail dog breeds. PLoS Genet 14:e1007850

[21] De Decker S, Rohdin C, Gutierrez-Quintana R (2024) Vertebral and spinal malformations in small brachycephalic dog breeds: Current knowledge and remaining questions. Veterinary Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2024.106095

[22] Roedler FS, Pohl S, Oechtering GU (2013) How does severe brachycephaly affect dog ’ s lives ? Results of a structured preoperative owner questionnaire. The Veterinary Journal 198:606–610

[23] Hall EJ, Carter AJ, Chico G, Bradbury J, Gentle LK, Barfield D, O’neill DG (2022) Risk Factors for Severe and Fatal Heat-Related Illness in UK Dogs—A VetCompass Study. Vet Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9050231

[24] Tripovich JS, Wilson B, McGreevy PD, Quain A (2023) Incidence and risk factors of heat-related illness in dogs from New South Wales, Australia (1997–2017). Aust Vet J 101:490–501

[25] O’Neill DG, Pegram C, Crocker P, Brodbelt DC, Church DB, Packer RMA (2020) Unravelling the health status of brachycephalic dogs in the UK using multivariable analysis. Sci Rep 10(1): 17251

[26] International Collaborative on Extreme Conformations in Dogs (ICECDogs) (2024) Reducing the Negative Impacts of Extreme Conformations on Dog Health and Welfare. https://www.icecdogs.com/home/position-statements. Accessed 27 Apr 2025