In contrast to birds and mammals, reptiles have evolved as ectotherms – animals who regulate their body temperature to suit the temperature around them. They are not poikilothermic (cold-blooded) as most people commonly believe i.e., while their body temperature is dependent upon external heat sources rather than internal heat production, most are capable of very precise control of their body temperature. This is achieved by:

- Movement between a heat source (e.g., sunlight, warm substrate) and a cool spot (e.g., shade, water, or burrow)

- Postural adjustments (e.g., changes in body volume, shape orientation or posture)

- Physiological responses e.g., heat production in muscle in some species, colour changes, circulatory changes, or mouth-gaping to increase water evaporation from the mucous membranes (the tissue that lines the mouth, digestive and respiratory tracts, etc).

Because reptiles are ectotherms, they have a slow metabolic rate – as little as 1/7 of the rate of a similarly sized mammal. They cannot live in very cold conditions – because of this, they are not as widespread as endotherms (e.g., mammals), but have survived and evolved for millions of years.

There are two important consequences of ectothermy are highly relevant to husbandry:

- Reptiles have a low rate of energy expenditure. Because energy derived from food or fat stores is not needed to maintain body temperature, the food requirements of reptiles are lower than endothermic animals. The food requirement is further lowered by behaviours that entail relatively long periods of inactivity i.e., living in an enclosure.

- Maintaining a prolonged constant body temperature is not required for most reptiles and can actually be harmful. The body temperature of reptiles varies between species, body size, during different seasons, while feeding, breeding, and with disease.

An important concept in reptile husbandry therefore revolves around maintaining the animal at their Preferred Body Temperature (PBT). This is the temperature at which that individual animal is functioning at its best, given its species, age, reproductive status, nutritional status, and health.

Because the PBT for any individual animal cannot be calculated exactly (outside of a laboratory), it is important to maintain the animal within a temperature gradient that includes their Preferred Optimal Thermal Zone (POTZ).

| Species | PBT (°C) | POTZ (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern long-necked turtle | 26 | 22-26 |

| Short-neck turtles | 26 | 25-28 |

| Children’s python | 30-33 | 26-32 |

| Carpet python | 29-33 | 20-32 |

| Diamond python | 29 | 20-32 |

| Green tree python | 32 | 20-32 |

| Common eastern blue tongue lizard | 28-32 | 28-32 |

| Bearded dragon | 35-39 | 28-40 |

| Lace monitor | 35 | 30-40 |

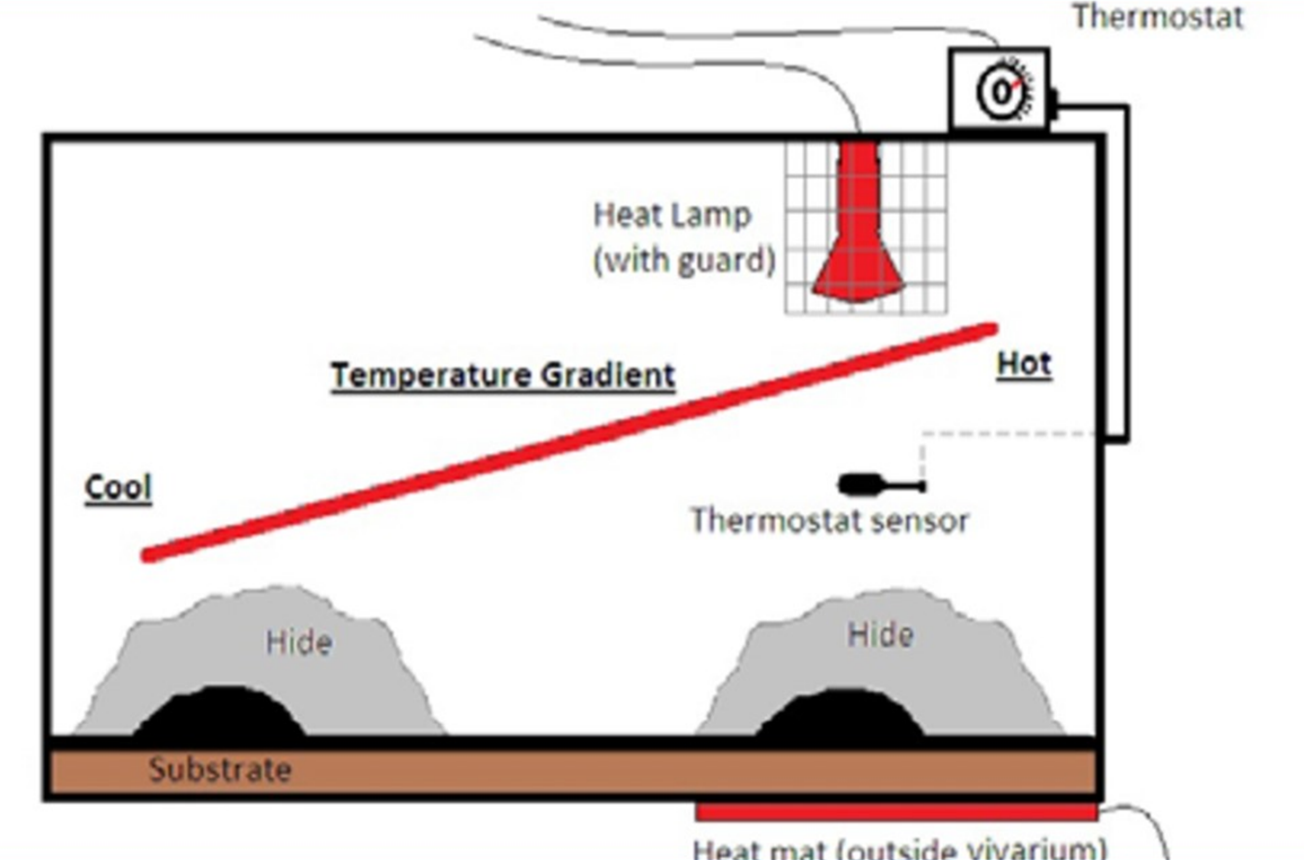

To maintain your reptile within their Preferred Optimal Thermal Zone in an indoor enclosure, you will need to provide a heat source. The type of heat can be:

- Radiant (from above) e.g., a heat lamp.

- Convective (from below) e.g., a heat mat.

Reptiles who are active during the day, or who live in trees, require a radiant heat source. Nocturnally active and/or predominately terrestrial species may prefer convective heat.

Just as in the wild, a daily temperature cycle (or access to shade / basking spots) is desirable. Heating sources available include infrared lamps, regular incandescent globes, thermal tape or cord, and ceramic globes. Thermal gradients can be arranged using these sources and a variety of shelters.

References

Carmel B, Johnson R (2014) A guide to health and disease in reptiles & amphibians. Reptile Publications, Burleigh

O’Malley B (2017) Anatomy and Physiology of Reptiles. In: Doneley B, Monks D, Johnson R, Carmel B (eds) Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice. Wiley-Blackwell, pp 15–32